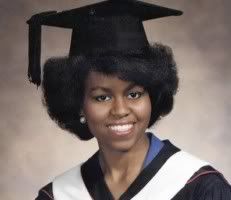

Myhell Okhrana before she started pretending to be bourgeois and white.

TheBlaze.com exposes the Shrew-In-Chieftess as a racist commie moron from way back:

Princeton, 1984.

Michelle Obama attends and promotes a “Black Solidarity” event for

guest lecturer Manning Marable, who was, according to Cornel West,

probably “the best known black Marxist in the country.”

The event is the work of the Third World Center (TWC), a campus group

whose board membership is exclusively reserved for minorities.

A

classmate of Michelle’s identified her to TheBlaze as the second person

on the left. Article/photograph taken from The Daily Princetonian –

Vol. CVIII, No. 107 November 6, 1984

–

Michelle Obama (Robinson at the time) was one of those 19 board

members and a leader of the organization. She helped to dispense what

was, in today’s dollars, a $30,000 budget. Of the 19 elected positions

on the board, there were two reserved spots for each of the five ethnic

groups TWC purported to represent: Asian, Black, Chicano, Puerto Rican,

and Native American.

Copy of TWC constitution showing board member requirements. (The Princeton Archives)

The board also had representatives from the various minority

organizations on campus, including Accion Puertorriquena y Amigos, the

Asian-American Students Association, the Black Graduate Caucus, and the

Chicano Caucus, among others. She also fundraised for the TWC by

participating in its African-themed fashion show and fundraisers (see picture here).

It was a controversial and racially-charged organization. And in

looking at the group’s racial focus before and during Michelle’s tenure,

we get a glimpse of her priorities while at Princeton.

Daily Princetonian article showing Michelle as a board member.

“White Students on This Campus Are Racist”

If ever there was an example of the TWC governing board’s obsession

with race, an editorial from October 21, 1981 is it. The members took

great offense to an op-ed titled “Rebuilding Race Relations,” calling

the article “racist, offensive, and inaccurate” for daring to question

the group’s true commitment and to present a thesis on race relations

counter to its own.

“The word RE-building implies that race relations once existed and, for some mysterious reasons, fell apart … ,” the board wrote in a scathing letter to the editor.

“We, on the other hand, believe that race relations have never been

and still are not at a satisfactory level. We are not RE-building. We

cannot RE-build something that never existed in the first place.”

“Don’t hide behind excuses such as a lack of effort [to integrate

with the Princeton campus] on our part,” the revealing letter added.“The bottom line is that white students on this campus are racist, but they may not realize it.” [Emphasis added]

Princeton itself, however, was concerned about the self-segregation

by black students and proposed reforms to counter it, including no

longer permitting black students to all room together in one dorm and

integrating black freshmen into the general student body. The TWC

strenuously opposed all of these reforms, arguing that integration of

non-white students would harm the “support system” available to them,

especially blacks. (Julie Newton, “TWC criticizes CURL plan: Minority strife would worsen,” The Daily Princetonian, October 21, 1981).

While Michelle was not a part of the board in 1981, as a board member

of the Third World Center starting on April 7, 1983 she joined in a

different racially-charged statement reproaching the college for not

doing enough to hire “Latino administrators.” In a letter a few weeks

later, the TWC attacked Princeton’s administration for not replacing

Hector Delgado, a minority dean of students.

“This search needs to produce another experienced individual who is

of minority background, preferably Latino, and who will be responsive to

the concerns of Third World Center as well as the student body at

large,” the TWC’s governing board wrote.

Others on campus took notice of the group’s calls and expressed concern.

For example, Fred Foote — the editor of Prospect magazine, a

conservative monthly publication — criticized the TWC and Delgado for

their obsessive focus on race.

“[Delgado’s] penchant for drawing campus issues along racial lines—a

penchant shared by the TWC and The Daily Princetonian—is the chief cause of racial strife on campus,” he wrote.

A Culture of Racial Focus

The TWC’s racialism extended beyond who could become an officer in

the group . Although the TWC served a number of roles on campus and was a

hangout spot for minorities, its focus was mostly political. Its

various constitutions make this clear. To quote the 1983 version:

The term ‘Third World’ implies[,] for us, those nations

who have fallen victim to the oppression and exploitation of the world

economic order. This includes the peoples of color of the United States,

as they too have been victims of a brutal and racist economic structure

which exploited and still exploits the labor of such groups as Asians,

Blacks, and Chicanos, and invaded and still occupies the homelands of

such groups as the Puerto Ricans, American Indians, and native Hawaiian

people. We therefore find it necessary to reeducate ourselves to the

various forms of exploitation and oppression. We must strive to

understand more than just the basics of human rights. We must seek to

understand the historical roots and contemporary ramifications of racism

if Third World people are to liberate themselves from the economic and

social chains they find themselves in.

An early copy of the TWC’s constitution. (The Princeton Archives)

It adds in another version:

“The Center is not only a social facility, it has become a

place of educational and cultural activity in conjunction with its

political purpose. Because the term Third World is inherently political,

it is necessary that we be active in political work and in educating

ourselves to the various forms of exploitation and oppression. We must

strive to understand more than just the basics of human rights. We must

look for the underlying conditions faced by our peoples and seek

alternative modes of economic and political structures so that Third

World peoples and their nations will no longer be agents and pawns of

the two superpowers (the United States and Russia.)”

Another copy of the constitution and the preamble. (The Princeton Archives)

The Center also opposed the “ruling class values and culture that characterizes Princeton University.”

In November 1984, TWC’s board demanded that non-white students should

have the right to bar whites from their meetings on campus. They also

demanded minorities-only meetings with the deans. (John Hurley, “Black students, university debate closed meeting policy,”

The Daily Princetonian, November 29, 1984). The ban was frankly

unnecessary, since whites were made to feel unwelcome at the meetings if

they were invited at all, but the TWC continued to press for it,

arguing, too, that blacks ought to be able to bar whites from attending

events aimed at discussion of “sensitive” racial issues.

“The administration, by denying us these [blacks-only] meetings, is

saying that we don’t have specific needs that have to be addressed this

way,” David Jackson, ’87, a fellow TWC member, told the Daily Princetonian after the university officials finally rejected its proposal to hold racially limited meetings.

But despite the radical and racialist character of the TWC, Michelle

Robinson was an active participant and may have been attracted by that

very radicalism.

“The Third World Center was our life,” Angela Acree, her best friend at Princeton, told The Boston Globe in June 2008. “We hung out there, we partied there, we studied there [in Liberation Hall].”

“Not a day went by that I did not see Michelle at the Center,” Czerni Brasuelle, TWC’s director at the time, told the Daily Princetonian in its November 5, 2008 issue.

Brasuelle, director of the Third World Center from 1981 to 1983 and a

friend and mentor to Michelle during and after Princeton, was herself

no stranger to controversy. According to a Daily Princetonian columnist,

she described the campus climate as “racist” and worried about “a lack

of understanding of Third World [non-white] people.” (Barton Gellman,

“Rebuilding Race Relations,” Daily Princetonian, October 16, 1981). In

May 1983, Brasuelle joined calls for a minority dean,

writing that “[Princeton] cannot afford to ignore our commitment to

Affirmative Action with token representation of Latinos on the

administrative level.” Michelle’s mentor left Princeton for a position

as vice president of academic affairs at Kentucky State University at

the end of 1983.

In April 1983, the Third World Center held an emergency meeting where

it approved a draft statement, prepared jointly with the student

government’s race relations committee, calling for racial preferences

and set-asides in the hiring of administrators.

“There should be someone representing Third World views in the

administration,” explained Raghu Murthy ,’85, who sat on the board with

Michelle. (Daily Princetonian, May 6, 1983). The TWC wanted one of its

board members to be given a vote and a voice in the administrative

hiring process. (Daily Princetonian, September 20, 1983). Ultimately,

Dean of Students Eugene Lowe caved, agreeing he would “make an effort to

identify some candidates who are of Latino background.” (Daily

Princetonian, September 20, 1983.)

For the TWC, this departure set off alarm bells because it meant

someone more moderate might be appointed to run the Center. TWC members

demanded that they be given representation on its board. Michelle

Robinson joined a statement saying that students associated with the center be given a role in picking its director and was quoted in the Daily Princetonian as demanding that the dean place more TWC members on the search committee.

“We Saw a Need to Address Issues of Race Relations on a Continuing Basis…”

As a member of the Princeton student government’s standing committee on race relations, Michelle signed another provocative statement, recounting the history of the TWC and offering insight into its focus.

“We saw a need to address issues of race relations on a continuing

basis … .We saw the need to realize that situations, issues, and

problems involving race relations occur everyday.” She even helped to

“organize a rally to raise the question of [minority] representation in

the Dean of Students Office,” according to the statement.

The TWC bemoaned the “institutional racism” on campus and pushed for

more minority students. A frequent participant in TWC events was

assistant dean Delgado, who claimed that Princeton was excluding

minorities from admissions or hiring on campus, presumably because of

its racism.

“Sometimes the institution gives criteria which exclude certain people,” Delgado told the Daily Princetonian in December 1982

at one of the numerous TWC forums on racism. “There are only five black

tenured faculty, no Chicanos, no Puerto Ricans.” (Michelle Robinson

would go on to make a similar argument as a student at Harvard Law

School and in her thesis.)

Unfortunately the calls for more diversity did not extend to

diversity of thought within the black Princeton community. Blacks who

disagreed with the race-baiting consensus and need for agitation among

the campus’s minority activists were often made to feel like “sellouts”

by the TWC members, who sought to enforce a racial orthodoxy.

Crystal Nix Hines ’85, who became the first black editor of the Daily Princetonian, had a run-in with Michelle that reflects the activists’ mentality. As she would recall to the New York Times in 2008, Michelle wanted her not to run an article that characterized a black politician in a negative way.

“You need to make sure that a story like that doesn’t run again,” the

former editor remembered her saying. (Hines could not be reached for

comment, but the likely story was this profile of Harold Washington, the controversial first black mayor of Chicago and a role model to both Michelle and Barack Obama.)

Crystal wrote about her experience at Princeton in a January 7, 1983

op-ed. She mentioned a “series of run-ins with the type of student who

implied that my involvement with white-dominated organizations,” and her

friendships with whites, were tantamount to “selling-out.” Crystal

became involved in the Third World Center and the Organization of Black

Unity, both environments in which Princeton’s alleged racism was

stressed.

“They prepared me for racism from students, professors, and from the

institutions itself. Above all, they urged me to be a part of the black

community[,] which they said would be sensitive to my needs and aware of

the problems I would face as a black student at a predominately [sic]

white institution.”

Robin Givhan,’86, described TWC as follows:

“I always felt like the Third World Center was, for a lot

of black students, really, the center of their social world,” says

Givhan. “There were definitely black students who joined clubs, who were

very much part of the wider social world, but there were some [who]

really, I felt at the time, really sort of relied on the Third World

Center as this kind of security blanket. And my feeling was always that I

kind of needed or wanted to pop into the Third World Center as a way of

saying, yeah, I’m black, I know that, I’m aware of that, but I never

wanted or was interested in that being the center of things for me. If

I’d wanted that experience, I would have gone to Howard or Spellman.”

(“Michelle: A Biography,” Mundy, 85-86)

Givhan remembers getting the impression from one Third World Center

speaker that “if you didn’t believe what I believe, or operate the way I

operate, you’re denying that you’re black. I came back to my dorm room

and was in tears, relating my experience to my roommate, who was Chinese

American.” (Mundy, 86)

TWC’s Role in Bringing Radicals to Campus

In cooperation with the Organization of Black Unity, to which

Michelle also belonged, the TWC brought a number of terrorists and

radicals to campus. We don’t know which of these events she attended,

but it was probably more than a few, especially after she became a TWC

board member. According to the heavily favorable “Michelle: A

Biography”, she “spent much of her free time at the center, where, among

other events, she attended seminars that featured the last surviving

Scottsboro boy—a member of nine black Southerners who were falsely

accused of raping two white women in the 1930s—and another featuring

Rosa Parks.” (Mundy, 114).

These are just a few of such events hosted or promoted by the TWC while Michelle was a student:

- In November 1981, Hassan Rahman, the Palestinian Liberation

Organization’s deputy observer to the U.N., came to campus. At this

remarkable event, sponsors TWC and OBU segregated the audience along

racial lines and had students serving as security guards and searching

bags. (Jay Appelbaum, “Students decry ‘security’ at PLO speech,” Daily Princetonian, November 30, 1981).

- In February 1982, the Center sponsored David Johnson, a

representative of El Salvador’s Democratic Revolutionary Front (FDR),

the political wing of the terrorist group FMLN. (Stona J. Fitch, “Salvadoran opponent speaks. Demands end to U.S. military, economic aid,”

Daily Princetonian, February 26, 1982). That very day the TWC created a

task force intended to “draw attention to the link between U.S. policy

in El Salvador and other forms of oppression.” (Meryl Kessler, “TWC

forms task force to oppose U.S. intervention in El Salvador,” Daily

Princetonian, February 26, 1982). Members also signed a petition that

opposed the Reagan administration’s involvement in El Salvador and, in

particular, the military aid to its pro-American, anti-Communist

government. (Tom McLaughlin, “TWC members petition against Reagan,” Daily Princetonian, February 23, 1982)

- The following month, TWC sponsored a trip

for 20 Princeton students Puerto Rico in order “to examine student

movements, Puerto Rican nationalism, family structure, the role of

women, and the U.S. military activities on the island of Vieques.” (The

island off Puerto Rico — and the military’s presence on it — were a

cause celebre among the political left. After years of agitating, the

Navy’s extensive live-fire exercises on the island were ended due to

political pressures.)

- In

April, the Daily Princetonian reported, the Organization of Black Unity

sent two representatives to Yale for a weekend symposium on the

problems of black Ivy League students. Kwame Toure, a.k.a. Stokely

Carmichael, a member of the All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party and a

leader of the Black Panthers in the 1960s, gave a presentation

emphasizing “the need for the organization of the black masses and the

active participation required from black students,” said Janette Payne, ’84, who attended the conference.

- In late April 1982, the TWC and the campus’s Minority Recruitment

Office hosted the April Hosting Cultural Show, at which William T.

Murphy, a member of the Organization of Black Unity’s board, launched

into an attack on white people by quoting Malcolm X, the subject of his

senior thesis that year. One student, Paul Russo ’85, walked out and

wrote a letter titled “Fostering Hate” to the campus paper.

Murphy refused to apologize and attacked Russo in a letter of his own,

accusing him of being an oppressor and blind to the racism on campus.

(William T. Murphy ’82, “The past and present reality of Malcolm X,”

Daily Princetonian, May 3, 1982).

- Michelle also likely participated in Black Solidarity Day the

following semester, where black students en masse absented themselves

from class to dramatize what they considered blacks’ largely ignored

contributions to society. Protestors carried signs saying “The struggle

continues” and “Liberation through unity and struggle.” (Crystal Nix,

“Procession symbolizes ‘continuing struggle,’ Daily Princetonian,

November 2, 1982).

- On April 15, the TWC hosted Michael Manley,

the former prime minister of Jamaica. Manley, a committed socialist who

dubiously denied that he was a Marxist, headed the pro-Castro National

Liberation Party and later in 1983 opposed Reagan’s removal of the

Marxist thug Maurice Bishop from power in neighboring Grenada.

- In April 27-28, 1983, the TWC hosted a symposium

praising the work and life of Clemente Soto Velez, another

Puerto Rican nationalist and poet. In 1936, Soto Vélez was arrested by

United States authorities and charged with conspiracy to overthrow the

U.S. government. He served a six-year prison term. Soto Velez then

returned to Puerto Rico, only to be arrested once more for violating the

conditions of his release. In 1942, after another two years in prison,

he was released but forbidden to return to Puerto Rico. (“Clemente Soto

Velez, Puerto Rican Poet, 89,” New York Times, April 17, 1993).

- In September 1983, the TWC hosted Princeton’s president, William G. Bowen.

Although Michelle has habitually made her alma mater seem racist in her

writings and public statements, Bowen was actually the architect of

Princeton’s racial preferences and an outspoken advocate of them. He

even went on to co-author a book, “The Shape of the River: Long-Term

Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions,” about

them with President Derek Bok of Harvard. Seeking minority applicants

would be the “responsibility of everyone in the admissions office,” Bowen told

the TWC. To attack Bowen, president of Princeton from 1972-1988, and

his allegedly racist Princeton, was to attack a straw man. Both his

successor and his predecessor were just as enthusiastic about

preferences.

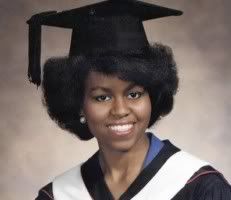

- In November, Michelle likely attended a Black Solidarity Day (BSD) event. The photograph

appears to include her, at right. Black Solidarity Day, founded in 1969

during the height of the black power movement, tries to highlight what

would happen if blacks absented themselves from American life.

Celebrated the day before Election Day, BSD reminds blacks of their

political power.

- Four days later, it played host

to the pro-Castro writer and ethnographer Miguel Barnet in Liberation

Hall. He criticized the American media for its coverage of El Salvador,

where the Marxist FMLN continued to fight the country’s legitimate

government. “If there are guerillas in El Salvador, it is because the

people want justice,” he told the TWC.

- On April 20, the TWC held a conference on “being black.”

- In September 1984, Arcadio Diaz-Quinones,

a Puerto Rican nationalist, specialist in “post-colonial” studies, and

Latin American studies professor, became interim director of the Third

World Center. (Later in the decade, he helped an illegal immigrant,

Harold Fernandez, conceal his status at Princeton and eventually help

him secure financial aid, as revealed in Fernandez’s memoirs.) (Joseph

Berger, “An Undocumented Princetonian,” The New York Times, January 3,

2010).

- In November of that year, Malcolm X biographer Manning Marable spoke

to TWC’s annual Black Solidarity event. He encouraged the audience to

vote for Reagan’s opponent Walter Mondale, who “[i]n the context of

black solidarity” was both “a lesser evil” and “a choice against Reagan,

Reaganism, and racism.” Marable also sided with the Marxist Nicaraguan

dictatorship, encouraging black Americans to express solidarity with

“the righteous movements of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the New Jewel

Movement in Grenada, the guerillas of El Salvador, and especially, our

brothers and sisters in South Africa.” (D.E. Williams, Daily

Princetonian, November 6, 1984)

Other guests during Michelle’s time at Princeton included the anti-Friedmanite, anti-Hayekian economist Albert Hirschmann (February 16, 1983),

the Chilean left-wing activist-turned-poet and playwright Ariel

Dorfman, and Jamaican development economist George Beckford, who blamed

Caribbean poverty on neocolonialism. Also invited and came was Paulo

Freire, the founder of Marxist pedagogic theory. (“Freire’s main idea is

that the central contradiction of every society is between the

‘oppressors’ and the ‘oppressed’ and that revolution should resolve

their conflict,” writes education reformer Sol Stern.)

Professor Diaz-Quinones, the interim director of the TWC in 1983 noted

“the growing consciousness of Third World countries and the

relationship minority students felt to certain threads in their

history.” Blacks and other non-white students, then, weren’t American in

any larger sense, the thinking went, because of America’s institutional

racism. The TWC provided programs that “link the ‘historical legacy of

racism on both sides.’” Recalling its own legacy on its tenth

anniversary, Center representatives wrote:

In the spring of 1971, many of the issues facing Third

World people at Princeton and across the country were similar to those

we face today. The country was in recession, and a Republican

administration was attacking the social and political gains of the Civil

Rights and Black Power movements.” (A Luta Continua: A History of the

Third World Center at Princeton, 1971-1981).

“Black Drama”: Making Race a Class

The Center also pushed for “institutional changes” to combat the alleged racism on campus. (The Daily Princetonian,

October 6, 1982, p. 3). According to a document obtained through the

Princeton archives, the TWC sought to implement ethnic studies programs

and get more minority faculty and students on campus. Among their

recommendations was the creation of the Afro-American Studies Program,

which was quickly established and which Michelle joined. Her thesis

advisor, Howard Taylor, was the program’s director. According to course

descriptions taken from the Princeton archives, the push was successful:

AAS 306: The Black Woman: This course seeks to go beyond

the broad analysis that has characterized the study of the black woman.

Students critically evaluate the historical background and status of the

black woman in African society and her transition into slavery; and the

many roles the black woman plays in contemporary society. The course

looks at the basic institutions that impinge on the black woman’s life,

and an attempt is made to determine how successful she has been in

maintaining her identity.

AAS 201: Introduction to the Afro-American Experience: The course

deals with a phase of black history which ends where the courses of this

type begin. It is not an exploration into slave colonial history; but

rather, an expose of the barrenness of earlier concentrations on the

African primitive and the black slave. The course seeks to promote a new

vision of the African ancestor, and, as such, focuses on the core and

genius of African civilizations, rather than emphasizing the African as

victim of the European imperalist [sic] enterprise. The course format

extends the historical framework within which to view the

African-American experience, and is intended to revise the conception of

African and African-American achievement and potential.

A January 1987 course guide provides further evidence:

January 1987 course guide shows the extent of the African-American studies program at Princeton. (The Princeton archives)

January 1987 course guide shows the extent of the African-American studies program at Princeton. (The Princeton archives)

For the first time ever, the college even offered a course on Swahili through the Third World Center as evidence of its diversified curriculum.

The Radical Fliers and “Oppression”

In case there was any doubt about the group’s radical focus, a flier from the time makes it clear it was all about “struggle”:

A flier for a TWC event that put’s the focus on “struggle.” (TheBlaze)

Another document from the center confirms that Michelle had to have known of the group’s radical focus, too:

“Oppression breeds resistance,” a document from the TWC states. (The Princeton archives)

“Oppression breeds resistance,” the document titled “A CALL TO ALL

THIRD WORLD STUDENTS TO STRUGGLE AGAINST ATTACKS ON THE THIRD WORLD

CENTER,” states. “The history of the peoples of the Third World, who

have suffered U.S. Imperialism, and of the oppressed nationalities

within the United States — Afro-Americans, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos,

Asians, and Native Americans — has been a history of oppression and

resistance. This is true for the Third World Community, which in this

instance includes students from the oppressed nationalities in the U.S.,

on Princeton University’s campus.”

Michelle would later write her senior thesis, which attracted national attention in 2008,

on that same kind of “oppression.” The 60-page thesis tends to

discredit the claim that race-based admissions policies or separate

groups actually foster diversity and integration at all. The future

First Lady mailed a questionnaire to 400 randomly selected black

Princeton alumni. Although the response rate was underwhelming, the

responses of the 89 black alumni who returned the questionnaire gave

reason for concern. The alums were asked whether they felt “much more

comfortable with Blacks,” “much more comfortable with Whites,” or “about

equally comfortable with Blacks and Whites,” in various contexts,

during three periods in their lives—pre-Princeton, Princeton, and

post-Princeton.

Far from encouraging racial tolerance, the number of black alumni who

said they felt “much more comfortable with Blacks” went up sharply

during their Princeton years, in comparison with their pre-college

lives, in categories like “Intellectual Comfort” (26% vs. 37%) and

“Social Comfort” (64% vs. 73%).

Michelle herself stated, “My experiences at Princeton have made me far more aware of my ‘Blackness’ than ever before.”