From dayofwrathdiesirae.blogspot.com:

In 1926, a small army of Catholic peasants who took on the name

"Cristeros" (followers of Christ) fought to regain religious freedom in

Mexico. Before they were through, as many as 50,000 men from every

socioeconomic background took up arms against the government.

The

"war" produced many religious refugees, some of whom came to El Paso.

The city welcomed the persecuted, and from this support stemmed the

founding of new seminaries and monasteries, which still exist today.

In

1917, President Plutarco Elías Calles and the former president, General

Álvaro Obregón, weakened the Catholic Church in Mexico by enforcing the

Articles of the 1857 constitution included in the 1917 version. Article

3 called for secular education in the schools, thus outlawing parochial

education. Article 5 closed all seminaries and convents. Article 24

forbade worship outside the physical borders of the church.

Article

27 prohibited religious groups from owning real estate, thus

nationalizing all Church property. Article 130 prohibited priests and

nuns from wearing religious vestments, but more importantly, it took

away from the clergy the rights of voting and speech, prohibiting the

criticism of government officials and comment on public affairs in

religious publications.

The closing of seminaries began during

the Mexican Revolution, leaving nuns and priests with no place to live

or work. The government also ruled that only Mexican born clergy would

be allowed to remain and participate in religious activities in Mexico.

By 1917, hundreds of religious had been expelled from Mexico or had fled

the country.

The Catholic Church did not want to retaliate

violently against the government, so from 1919 to 1926, they obeyed the

laws. However, in 1926, President Calles introduced legislation which

fined priests $250 for wearing religious vestments and imprisoned them

for five years for criticizing the government.

Archbishop of

Mexico, José María Mora y del Río, declared that the Catholic Church

could not accept the government's restraints. On July 31, 1926, the

archbishop suspended all public worship by ordering Mexican clergy to

refrain from administering any of the Church's sacraments.

The

Cristeros felt the only way to fight the government was to take up arms:

they were willing to become martyrs for their freedom of religion. Jean

Meyers, a French expert on this revolution, tells us about Cristeros

attending field masses, dressed in sandals and white garments and armed

with machetes. They knew that soldiers could attack them with machine

guns at any time.

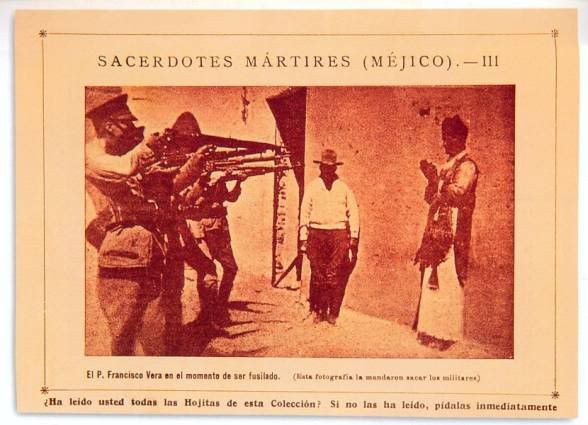

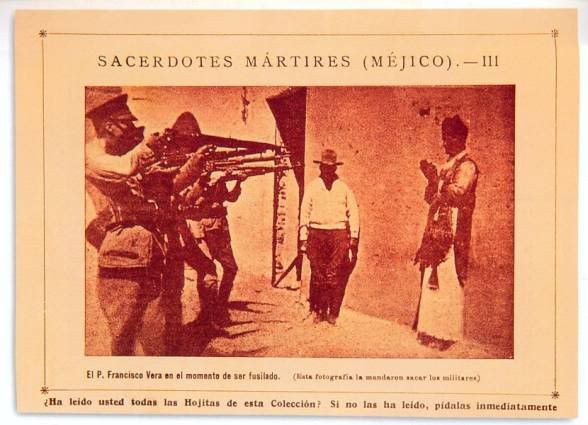

Many priests were martyred while celebrating

mass, either by being shot or beheaded. In a last affirmation of their

faith, the Cristeros would shout, "Viva Cristo Rey!" (Long Live Christ

the King!) just before dying.

Padre Miguel Agustin Pro was one of

the best known of the martyred priests. Pro used elaborate disguises so

that soldiers would not recognize him as a priest. Known for his

indefatigable sense of humor, he visited the faithful often dressed as a

beggar. He administered the sacraments, provided jokes and laughter,

and helped financially those in need. Rich families often received the

sacraments from Padre Pro in his disguise of businessman. Pro and his

brother, Humberto, were arrested for being erroneously linked to a car

bombing which injured ex-president Obregón. The car used in the bombing

was traced back to Humberto Pro, the previous owner.

Calles took

advantage of the opportunity to execute a priest publicly in an attempt

to discourage other priests from participating in politics. He ordered

Pro be shot at the police station and invited reporters to the

execution. Padre Pro carried a small crucifix and his rosary and held

his arms out forming a cross as he was shot. Pope John Paul II beatified

him on September 25, 1988.

Another martyr, San Pedro de Jesus

Maldonado Lucero, served the people's spiritual needs in Chihuahua,

Mexico. Maldonado attended seminary in Mexico in 1914, but the political

conflict forced him to leave. He came to El Paso and received his

ordination on January 25, 1918, from Bishop Anthony J. Schuler at St.

Patrick's Cathedral. Then he returned to Chihuahua to serve the

faithful.

After Calles' anti-Catholic laws were implemented in

1926, Maldonado became a government target for performing religious

ceremonies in private homes. He succeeded in celebrating night masses on

one ranch or another, performing marriages and baptisms and

administering other sacraments. In 1937 during Holy Week, the mayor and

soldiers in Santa Isabel, Chihuahua, arrested him and beat him to death

for defying government bans on hidden religious celebrations.

Maldonado's murderers used riffle butts to bash in his head and dislodge

an eye from its socket.

Like Maldonado, many other priests and

nuns along with ordinary Catholics, Mormons and Episcopalians left the

country and found refuge in border cities in the United States, among

them, El Paso. Patrick Cross writes that by 1929, some 25,000 priests in

approximately 12,000 parishes no longer could minister to the spiritual

needs of Mexican Catholics, over 10 million strong.

In a

personal interview, Dr. Jesus Cuellar, this writer's grandfather,

recalled that at the age of 13, in 1927, he was helping Father Gregorio

Paredes with a secret mass in a house in Guanajuato. After it concluded,

soldiers came looking for a place to feed and water their horses.

In

order to save the priest's life and to keep the Eucharist from

desecration, Cuellar took the Chalice containing the Eucharist and ran

out to hide it in a neighboring house. He and Father Paredes hid in a

basement for three days, waiting for the soldiers to leave.

Persecuted

Mexican Catholics received worldwide sympathy. Boston banned the new

religious regulations calling them "the most brutal tyranny." New York

parishioners crowded Catholic and Protestant churches to offer prayers

for a peaceful solution in Mexico.

El Paso Bishop Reverend

Anthony J. Schuler welcomed Juárez Catholics and even granted priests

permission to perform marriages and baptisms without requiring residency

for the Mexican citizens. Between 1926 and 1929, the number of people

attending services at El Paso Catholic churches doubled. A dramatic

increase in baptisms and marriages of people with Hispanic surnames at

Catholic churches suggested that downtown churches were serving great

numbers of Catholics from Mexico.

Since priests and nuns in

Mexico could no longer teach there, many of them came to El Paso. Three

nuns from the order of Perpetual Adoration and two from the Servants of

the Sacred Heart arrived in El Paso on August 2, 1926. Sacred Heart

Church received the nuns from the Sacred Heart Order with open arms.

Because

there was no Perpetual Adoration order in El Paso, Bishop Schuler

provided the funds for the foundation of such a monastery to train nuns.

Other exiled nuns from Mexico City and Guadalajara soon joined the

first nuns.

Reverend Mother María Concepción del Espíritu Santo

was in charge of the nuns who came from Guadalajara. She found a

suitable location for the monastery in a house at 1401 Magoffin. Along

with money from the diocese, the Catholic community raised funds and

helped pay $7,550 for the property in monthly installments.

Once

El Paso became a diocese in 1926, it was allowed to establish seminaries

and became the home to Franciscans at St. Anthony's Seminary at

Hastings and Crescent in 1935. Before this, the persecuted Franciscan

order of Michoacan, which had not had a seminary since 1910, had lived

in Santa Barbara, Calif., after their departure from Mexico.

The

monasteries and seminaries established at this time succeeded so well

that an additional Perpetual Adoration Monastery in the Lower Valley and

the Roger Bacon Seminary soon followed to house homeless priests and

nuns.

During the religious persecution, some Mexican nationals

who sought and found asylum in El Paso decided to stay here. However,

many returned to Mexico but continued to enroll their children in the

parochial schools here. Perhaps the trend of bringing children to school

across the border began when El Paso met those needs so many years ago.

Even

though Catholicism is no longer openly persecuted in Mexico, the

religious persecution of the 1920s is still felt. The government

prohibits priests from owning property, criticizing government officials

or commenting on public affairs. The state still does not recognize

weddings performed by priests.

In 2000, the Pope canonized 25

priests of the Cristero era, including San Maldonado. The blood of the

thousands of Cristeros and martyrs that flooded the land nourished the

spirits of those left behind; their courageous cry can still be heard in

the hearts of the faithful, "Viva Cristo Rey!"